Origins of the Native Brotherhood/Sisterhood Movement

The Native Brotherhood began in 1964 at Saskatchewan Penitentiary and soon spread to the other prairie provinces and finally to the rest of the country

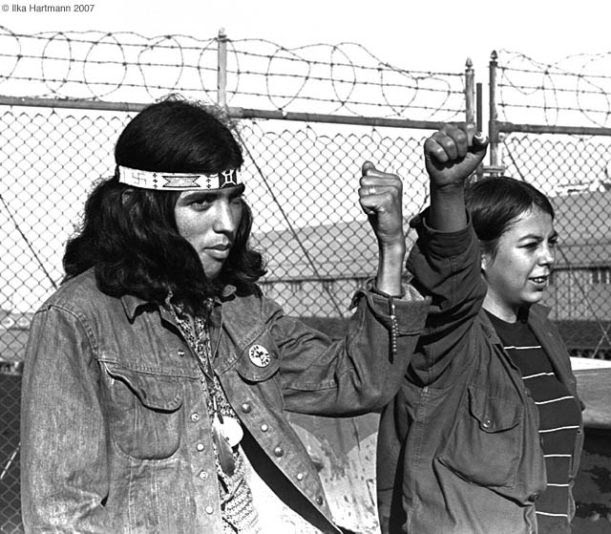

Post image source: Drumheller Native Brotherhood Newsletter, 1984

Ten Days of Prisoner Justice History: Day 7

The Warrior Spirit is alive and well… The legacy of our ancestors keeps alive the will to endure, to contemplate, and maintain the resilience that has become a characteristic of our people.”

Arrows to Freedom (1996), Drumheller Native Brotherhood Society Newsletter

The Native Brotherhood movement began in 1964 at the Saskatchewan Penitentiary in Prince Albert, SK. Because of the frequent transfer of prisoners (a common tactic of repression, often subverted by prisoners to their own ends), the Brotherhood quickly spread to institutions in Manitoba and Alberta, becoming a regional movement. By 1970, the movement had extended to Ontario, and shortly afterward to the rest of so-called Canada, including the Kingston Prison for Women (the only federal women’s prison at the time), where the Native Sisterhood emerged in 1976. The movement was informed by the vibrant Indigenous political activism of the 1960s/70s, including the American Indian Movement, some of whose leaders were themselves incarcerated.

The movement was a network of grassroots, prisoner-run organizations whose primary goal was to advocate for Indigenous rights behind bars and ensure that Indigenous prisoners had access to cultural and spiritual teachings and practices. Before the Brotherhood’s advocacy, not only were there no Indigenous-specific programs in prison, but Indigenous prisoners were prohibited from engaging in Indigenous ceremonies and spiritual practices such as smudging and sweats. This prohibition is part of a long history of criminalizing Indigenous cultural and spiritual practices, legislated by the Indian Act until 1951. The movement organized weekly activities and meetings for its members, liaising with the outside world to bring in Elders and community members to facilitate cultural activities, including powwows, feasts, beading, and leatherwork.

The Brotherhoods/Sisterhood also organized politically, demanding their own Indigenous alcohol and drug treatment programs, and protesting prison conditions through hunger and work strikes. In 1977, for example, members at the Saskatchewan Pen led 300 men in a four day sit-down strike to call attention to conditions that led to the death of three Indigenous prisoners in less than a week.

Importantly, writing was a central mode of resistance for the Brotherhood/Sisterhood. Each chapter had a newsletter, where members wrote poetry, cartoons, editorials, and letters, articulating trenchant critiques of the system and proposing solutions grounded in Indigenous self-determination. The newsletters circulated amongst members, offering support across institutions and furthering the aims of the movement.

Members also engaged in political advocacy on the outside, pushing for the establishment of Indigenous-run halfway houses, and calling upon Indigenous and Canadian governments to respond to the injustices faced by prisoners. Many continued their activism upon release. Joseph Mercredi, for example, engaged in a compelling protest to draw attention to prisoners’ rights, locking a ball & chain to his leg, mailing the key to the Prime Minister, and hitchhiking across the country to protest the injustice of incarceration.

By the late 1980s, Indigenous culture had been institutionalized by the Correctional Service of Canada, which adopted Indigenous-specific programming into its mandate. Such institutionalization serves as a cautionary tale about the ways in which colonial systems can absorb critique. It is important, however, to remember and honour the work of the Brotherhood/Sisterhood in upholding Indigenous rights and fighting tirelessly to create access to Indigenous cultural and spiritual traditions in the first place. While the Brotherhood/Sisterhood no longer officially exists by that name (having been replaced by “Aboriginal Wellness Committees”), Indigenous prisoners continue to organize and advocate for their rights, resisting conditions of settler colonial oppression endemic to the penal system.

Sources

Adema, Seth. (2012). “‘Our Destiny is Not Negotiable’: Native Brotherhoods and Decolonization in Ontario’s Federal Prisons, 1970-1982.” Left History 16.2, 35-51.

Adema, Seth. (2016). More than Stone and Iron: Indigenous History and Incarceration in Canada, 1834-1996. Dissertation. Wilfrid Laurier University.